Results-Driven Mental Health Treatment Model Expanding in Michigan

Julie Bitely

| 4 min read

Navigating a health care system that separates mental health from physical health can be difficult and confusing for patients. Combining treatment for both under one roof is the premise behind the Collaborative Care Model, an integrated approach that provides clinical support to primary care providers to better manage patients with behavioral health conditions. The model is twice as effective in treating depression in adults when compared to more traditional care and it’s growing in Michigan, due in part to incentives offered by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Although this model has been studied and proven effective since the early 2000s, its use was still limited, and Blue Cross wanted to accelerate its implementation in Michigan. In 2019, BCBSM had about 25 practices using the model and added an additional 54 in 2020. Training efforts and ongoing setup support helped to expand the model and are expected to bring on 75 additional new practices this year and 125 new practices in 2022. “The Collaborative Care Model is a significant change in medical care, and it really does work to help people get better,” said Dr. William Beecroft, medical director, Behavioral Health Strategy and Planning. Dr. Ed Deneke agrees. He’s the associate medical director, Adult Ambulatory Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry at the University of Michigan. He serves as a psychiatric consultant for Michigan Medicine clinics, an early adopter of the Collaborative Care Model since 2014. “If I see my PCP (primary care provider) and I have depression, I might get an appointment with a psychiatrist but have to wait two months,” Deneke said. “In that time, my life might have changed, and I can come up with all the excuses in the world to not go. By keeping it in-house with the primary care team … I think that means a lot for a lot of people.” In the face of a nationwide shortage of behavioral health providers, expanding access through Collaborative Care can help patients not only focus on their mental health, but their other medical conditions. “If you don’t treat depression, an individual who also has diabetes, COPD or another health issue really doesn’t have the energy, interest or ability to do the work necessary to get better,” Beecroft explained.

How it works

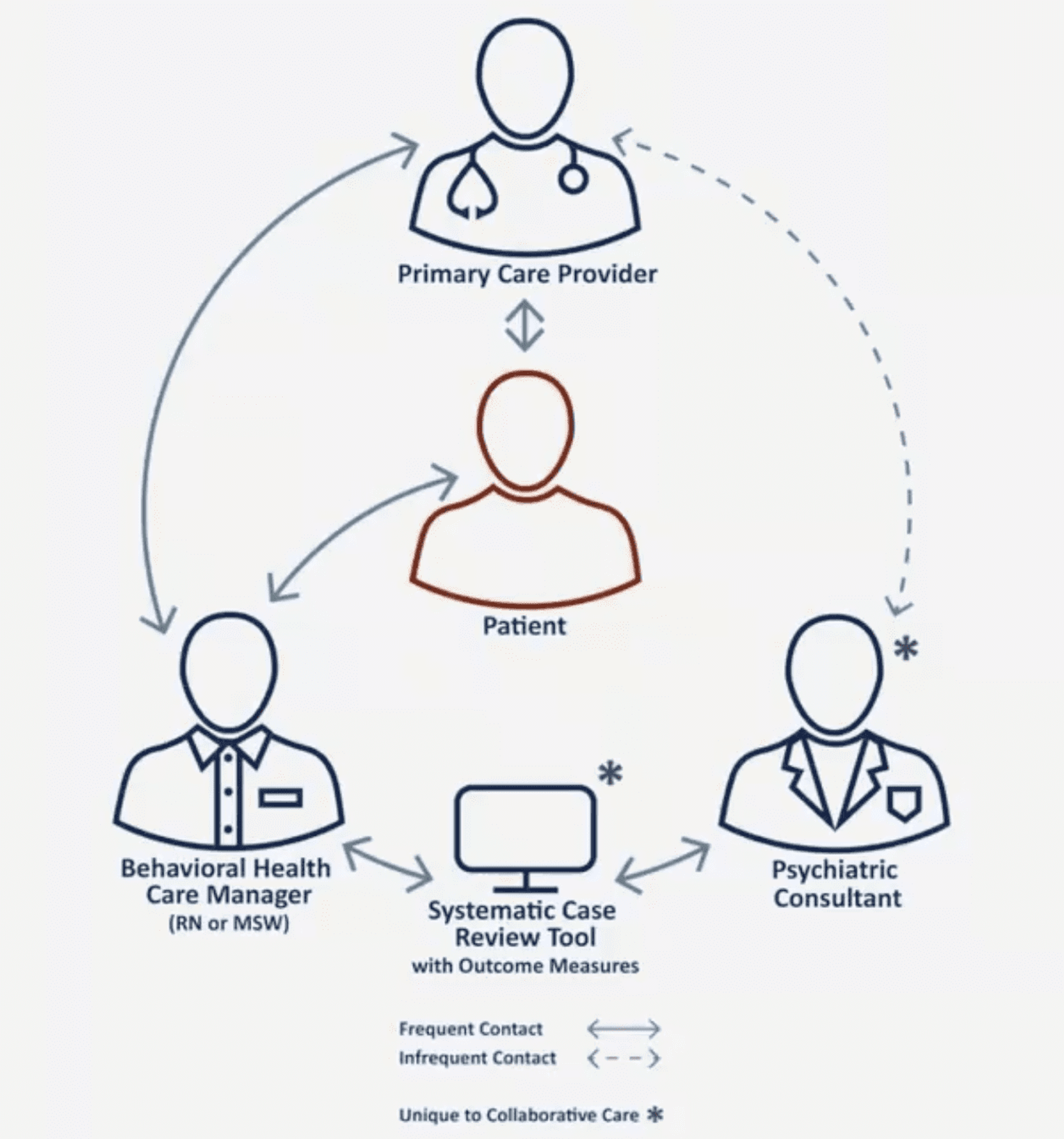

The Collaborative Care Model consists of a psychiatric consultant and behavioral health care manager supporting the patient’s primary care provider.

Patients see their doctor as usual. If the PCP identifies a patient dealing with depression or anxiety, they can refer them to the Collaborative Care program. An embedded care manager – often a social worker or registered nurse – consults with the patient and works with them to determine their needs and goals. The care manager consults with a psychiatrist through a systematic case review tool to discuss changes to medication or treatment, keeping the PCP looped in the entire time so everyone involved in the patient’s care knows what’s going on. The model provides benefits for patients and providers, Deneke explained, noting that clinics skeptical to implement the program often become its biggest cheerleaders after they take the leap. “About six months into the program, people (providers) can’t imagine life without it,” Deneke said. To encourage participation in this high-value program, members receiving these services pay only for the primary care office visit and do not have cost-share for the additional Collaborative Care Model support.

Why it’s different

With the Collaborative Care model, the behavioral health care manager serves as a bridge between the PCP and the psychiatric care patients often need to move forward. Because they work in the same office with the patient’s doctor, patients don’t need to go to a separate office and their care for mental and physical health needs are integrated. Ashley McClain, LMSW, ambulatory care social work supervisor, Behavioral Health Collaborative Care, Michigan Medicine works with patients as a care manager. She said a lower barrier to entry and trust in the PCP’s recommendations for treatment seem to make a difference for patients in following through with mental health care. “I’ve had more willingness from patients to get engaged,” McClain said. She’s able to connect patients to pharmacists and nutritionists for a truly team-based approach to care. McClain sets goals with patients and helps them put a plan in place. In addition to medication recommendations, McClain can also coach patients on other evidence-based interventions including coping mechanisms, behavioral activation, meditation, and exercise that may aid in the process of decreasing overall symptoms of depression or anxiety. Furthermore, she may assist patients in connecting to community resources such as individual psychotherapy or therapy groups. The model works well for depression and anxiety diagnoses, Deneke said. Cases of post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder and other mental health disorders might require more intensive care. There is also evidence that Collaborative Care is helpful in substance use disorder. Blue Cross hopes to explore opportunities to expand the model to this area. Still, for people with more intense needs, having a doctor engaged with the Collaborative Care model could help normalize conversations about mental health in general and help more people discover and accept the need for additional help. Related: